Is Cryopreservation -- the Freezing of Human Beings With Diseases to Revive Them When There's a Cure -- Actually Possible?

by www.SixWise.com

Members of the cryonics movement -- estimated at 1,000 strong

and growing -- are taking perhaps the biggest gamble a person

can take; that they will be frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately

after their death and later be brought back to life.

|

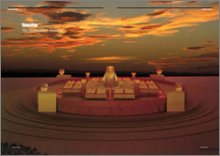

Architect Steven Valentine's "Timeship" --

a "life extension research and cryopreservation"

facility -- will house research laboratories, animal

and plant DNA, and as many as 10,000 frozen people.

|

About 142 people currently have their body or head held in

one of two cryonics storage facilities in the United States

-- Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona,

and the Cryonics Institute of Clinton Township, Michigan --

and many more have signed up. Among them are Baseball Hall

of Famer Ted Williams and a handful of wealthy U.S. and foreign

businessmen who have created "revival trusts" that

would allow them to reclaim their fortunes hundreds or thousands

of years down the road.

"This is going to be the century of immortality,"

says Stephen Valentine, an architect who has designed the

Timeship -- a "life extension research and cryopreservation"

facility that will house research laboratories, animal and

plant DNA, and as many as 10,000 frozen people.

"Children being born today are probably going to live

an average lifespan of 120 years. Their children, it is being

predicted, will never die. There will be a time when people

won't be able to comprehend the thought of not existing any

more and just becoming fertilizer," Valentine says.

How Does Cryopreservation Work?

In cryopreservation, a body is put in a glycerin-based solution,

cooled with dry ice, then held in a pool of liquid nitrogen

until the body temperature reaches minus-320 degrees Fahrenheit

(at which temperature all cell movement is stopped).

The idea is that people with incurable diseases could be

frozen today, then rewarmed decades later when medicine has

advanced and a cure is available.

|

A steel, liquid-nitrogen-filled capsule used for cryopreservation

at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale,

Arizona.

|

Currently, only certain cells and tissues, such as sperm

and embryos, can be frozen and successfully rewarmed. One

of the biggest hurdles facing the technology is how to stop

the formation of ice crystals, which damage cells.

New Research Suggests Cryopreservation IS Possible

Most cryonics centers require that interested parties register

and pay in advance of their death, anywhere from $28,000 to

$120,000. While some members opt to freeze their entire body,

others preserve only their heads, with the idea that their

consciousness will be transported into a "fresh"

body.

While critics claim the centers are offering false hope and

scamming people out of money, new research by University of

Helsinki researcher Anatoli Bogdan, Ph.D. suggests that the

entire human body could be cyropreserved without the formation

of damaging ice crystals.

"Damage of the cells occurs due to the extra-cellular

and intra-cellular ice formation, which leads to dehydration

and separation into the ice and concentrated unfrozen solution.

If we could, by slow cooling/warming, supercool and then warm

the cells without the crystallization of water then the cells

would be undamaged," Bogdan says.

His research looked into a form of water called "glassy

water," or low-density amorphous ice (LDA). The glassy

water, which is produced by slowly supercooling diluted aqueous

droplets, melts into a highly viscous water (HVW), which Bogdan

says could have important applications for cryonics:

"It may seem fantastic, but the fact that in aqueous

solution, [the] water component can be slowly supercooled

to the glassy state and warmed back without the crystallization

implies that, in principle, if the suitable cyroprotectant

is created, cells in plants and living matter could withstand

a large supercooling and survive."

The Ethics of Immortality

The details of a world where no one dies, or at least one

in which not dying is a possibility, raises an unforeseen

number of legal and ethical questions. For instance, would

someone who is pronounced dead and then later revived have

to pay back their life insurance? And doesn't the prospect

of cryopreservation already exclude those who are poor and

unable to afford it?

At the very least, the notion of cryopreservation would alter

the very definition of death.

"Death is just the point at current technology when

the doctor gives up," said David Ettinger, whose father,

Robert Ettinger, is said to have founded the cryonics movement.

"It's a legal definition, not a medical one."

But while cryopreservation still remains, to most, something

out of a science fiction novel, Valentine views it as a natural

progression of humans' innate desire to live longer:

"Since the beginning of time we've done everything we

can to make ourselves live longer. We've invented vaccines.

We've cured diseases. What do we do that for? So people can

live better and longer."

Recommended Reading

Aliens:

Really Now, How Likely Are They? If They Exist How Likely

is it They'd be Friendly?

Want

to Live Longer? Be Wealthier? And Happier? Here is the One

PROVEN Secret: Reading!

Sources

Science

Daily June 20, 2006

Guardian

Unlimited: House of the Temporarily Dead

The

Wall Street Journal Online January 21, 2006

ABC

News: Would Freezing Ted Williams Really Work?